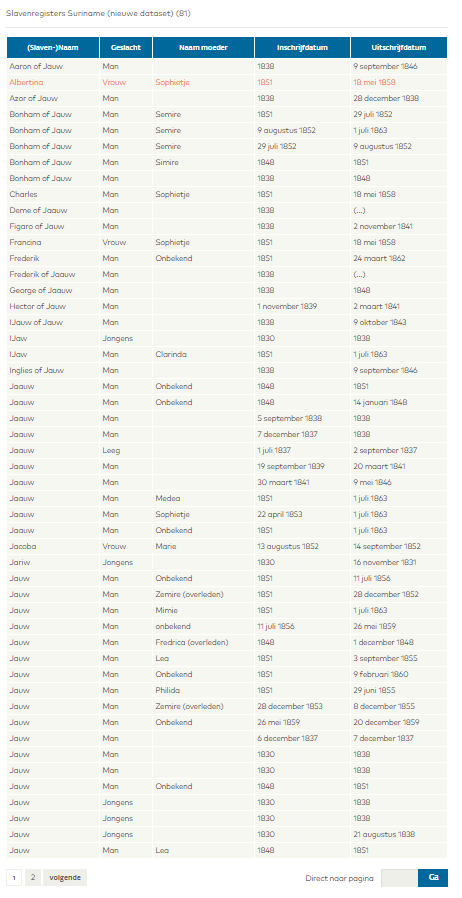

Even though a lot of historical records have been digitized, researching your Surinamese family history can still be tricky at times. For instance, the enslaved Africans in Suriname only received a family name upon manumission or emancipation. This makes digging through the slave registries still a very tricky process. You constantly have to check and recheck that you’re actually looking at the right ancestor and not another enslaved person with the same first name. The official registries also didn’t mention paternal lineage. But I digress, because this post wasn’t supposed to be about the difficulties of researching your family history, but some of the tidbits that I wish actual historical experts would delve a little bit more into.

Akan namedays

While searching through all the names you will notice that most of the enslaved people had European first names, which falls completely in line with the custom of stripping the Africans of everything that reminded them of their black humanity. However, there were a minority of people that did either retain their original name or were given one that was from their ethnic group. These African names are predominantly Akan namedays. Several Kodjos, Ambas etc. were apparently able keep their African names. Some enslaved had a name of a day of the week. Zondag (Sunday) or Maandag (Monday) are not uncommon. This could be related to this Akan custom.

I remember a historian (M. Caprino) once saying during a t.v. program that it was predominantly the enslaved female cooks who were able to keep their African name. The colonial and plantation authorities were severely outnumbered, and therefore lived in constant fear of being attacked and killed. One of the ways they feared being killed was by being poisoned, because they knew the Africans had an enormous wealth of knowledge of herbal medicine. Therefore, they afforded their female cooks certain liberties to appease them, with one such liberty being the ability to keep their name or have the freedom to name their children whatever they wanted.

This liberty did come with a price. The paranoid authorities knew that they could still be poisoned, and that’s why they would have the children of the cook come in to ‘test’ the food first, before they would eat anything themselves. They knew that these black mothers would not risk killing their own children. And that was their way of still keeping control.

I don’t know if this has been researched and written down somewhere or if it’s a part of history that was only passed on orally. I don’t have any other source for it than the previously mentioned historian.

Islamic names

Ever since I read the book Servants of Allah by Sylviane Diouf which explores Islamic religious and cultural elements that the African diaspora was able to preserve, I have wondered is there were any of such elements within African Surinamese culture. After all, the Dutch and British also took people from African areas with a long historic Islamic tradition. That’s another research project that I wish someone would take on. In the archives you will come across names that, even I with my limited knowledge of Islam was able to recognize as such. They are much less in frequency than the Akan ones though. There are some Africans named after the prophet, some named a variation of Suleiman. There was an Abufar smuggled in and manumitted, which is another interesting piece of history. There are Achmets, and Osmans. I remember seeing someone named Abubakar once, but of course spelled differently. There were also a lot of female Adyubas, which is the Akan nameday for a woman born on a Monday. However, I also found a man, with the name Adjuba then being the Islamic version of Job. And probably more names, but these are the ones that I have seen and was able to recognize.

Others

There are also a lot of women named Ada, with Ada being an Igbo name. However, Ada could also be a European name. I also mentioned the name Toetoeba in my post about my great great grandmother and the post about the gruesome events that took place on plantation Nieuwland. These two Toetoebas are not the same as far as I have been able to determine. The name Mingo also sounds African. One of the men who revolted and who may be featured in an actual 18th century painting, was named as such. Buanga is another name I’ve come across that sounds African.

Free at last?

In Suriname, the Africans only received a last name upon manumission or during Emancipation in 1863. Did they have some say in the names they received? I’m not too sure, however there was regulation that forbid a manumitted or Emancipated person to receive an existing ‘European’ name, and therefore new names needed to be created.

At first there were a lot of ‘van-names’ (van means of in Dutch). As in for example Sarah van John Johnson, with Sarah being a woman manumitted by John Johnson. But let’s say Sarah would then also continue on to ‘own’ and manumit slaves, which wasn’t uncommon, those people would then receive the name Kwaku van Sarah van John Johnson. Now if Kwaku continued the trend? You can imagine that this wasn’t too handy. So people found other creative ways. It’s unclear to me which group, the enslaved or the previous ‘owners’, was the initiator of this trend. But this is what happened. Probably to keep some sort of relation with the previous ‘owner’, a name that was some sort of anagram of the owner’s name, a shortened version, or a translation of the name was given.

Take for example the Sephardic Jewish family name de la Parra, which translates to of the vineyard. Most of the people that were manumitted or emancipated by this family received a name that had something to do with wine (wijn in Dutch) or vinyards. Wijngaarde (vineyard), Wijnstek (vine cutting), Wijntuin (vine garden), Wijntak (vine branch), Druiventak (grape branch) are all examples of names with a notch to the de la Parra family. Lobo, another Sephardic Jewish family, gave the name Wolf, with Lobo being the Portuguese translation for wolf.

And there are many more examples. Levy with the letters rearranged became IJvel, Muller became Rellum, Kustner became Nerkust, Da Silva became Vasilda, Wilkens became Kenswil etc. Sometimes the people manumitted and emancipated with these new names were indeed descendant of these male owners. But there have also been many instances, including in several branches of my family tree, where that was not the case.

Very funny…!

The owner of plantation La Prosperite gave the emancipated of that plantation, names that predominantly started with the letter P. Pinas, Pierau, Pengel, Panka are some examples. These families still predominantly live in the region this plantation is located in. Pinas is nowadays considered to be what the name Johnson would be in America as in a name that a lot of people have. During the Suriname Covid-lockdown, some hilarity ensued regarding these P-names. To prevent large crowds, Surinamese citizens were only allowed to go out according to an alphabetic system. If your name started with A, B, C or D than you would go out on a Mondays etc. Of course on the day that families with the names starting with the letter P were allowed out, large crowds could not be avoided. Well at least, according to my Suriname people, who were able to see some humor in a very dire situation

And not so funny..:-(

There were also some derogatory names, both during and after slavery. I for example have male ancestor who carried the name Minosabi during slavery. This is Surinamese for ‘I don’t know’. An authoritative figure probably thought he was being funny by giving out such a name. My heart breaks for this ancestor who, not only had to endure the horrors of slavery, but was probably the butt of a joke anytime he was asked what his name was. There were also derogatory last names. Traag, Vadsig (both mean slow, or lazy in Dutch) come to mind. Changing these names wasn’t easy, because it required money. Money these people often didn’t have.

And the Maroons*?

They also eventually received a last name, even though I have seen records (birth, etc.) from the mid 20th century where some Maroons and Native Americans were still only registered by their first name only. I’m not too familiar with how their last names came about, but I would hope that they had more freedom. This is another subject that I wish people would research more. Take the name Aboikoni, a very popular Surinamese Maroon name, for example . It’s the name of one of the Surinamese granman (primary chief/king) families. Aboikoni translates to ‘The boy is smart’.

The Maroons had a similar societal structure as what they had known in Africa. There were, and still are different Maroon Ethnic groups, which are divided into different clans. From what I was able to read on the subject, when they first escaped, these clans were formed based on which African ethnic group they belonged to or from which plantation they managed to escape from. And maybe also other reasons, but these were the main ones I was able to find. When the clan was formed based on which plantation or owner they escaped from, they sometimes also gave the clan a derived name. For example the Maroons who managed to escape from the family Espinoza named their clan Pinasi, the ones escaped from the Cardoso family organized themselves in the Kadosu clan etc. A lot of the Maroons chose the same name as their clan. For more on this, see: https://kulanu.org/communities/suriname/among-maroons-discoveries-color-judaism-slavery/

*Maroons: I’ve stated this before on my blog. In Suriname we were taught that Maroon was an offensive word. It stems from the word cimarron which means runaway cattle. Referring to people as cattle is offensive. However, to my knowledge there’s no other word in English to refer to descendants of people who managed to escape slavery.

Also see:

Letter to Serafina

Rebel Faces

Lurid finds

Nursery Rhymes Nostalgia, for a Surinamese folksong about the Akan namedays

Very interesting post.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you so much for the compliment, and for taking the rime to read once again. It’s very much appreciated..:-)

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you for a very interesting post. You raise interesting questions that historians should take up. In some parts of India, it is the custom to name children after the day of the week they were born on, as well.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Yes, there is so much regarding Surinamese history that still needs to be explored… Yes, the practice of naming someone after a day of the week, is common in some east European countries as well.

LikeLiked by 1 person